The Grumman Gulfhawk, Dulles Airport Collection

One of the most exciting aerobatic aircraft of the 1930s and '40s, the Grumman Gulfhawk II was built for retired naval aviator and air show pilot Al Williams. As head of the Gulf Oil Company's aviation department, Williams flew in military and civilian air shows around the country, performing precision aerobatics and dive-bombing maneuvers to promote military aviation during the interwar years.

The sturdy civilian biplane, with its strong aluminum monocoque fuselage and Wright Cyclone engine, nearly matched the Grumman F3F standard Navy fighter, which was operational at the time. It took its orange paint scheme from Williams' Curtiss 1A Gulfhawk, also in the Smithsonian's collection. Williams personally piloted the Gulfhawk II on its last flight in 1948 to Washington's National Airport.

Gift of Gulf Oil Corporation

Manufacturer: Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation

Date: 1936

Country of Origin: United States of America

Dimensions:

Wingspan: 8.7 m (28 ft 7 in)

Length: 7 m (23 ft)

Height: 3.1 m (10 ft)

Weight, aerobatic: 1,625 kg (3,583 lb)

Weight, gross: 1,903 kg (4,195 lb)

Top speed: 467 km/h (290 mph)

Engine: Wright Cyclone R-1820-G1, 1,000 hp

Materials:

Fuselage: steel tube with aluminum alloy Wings: aluminum spars and ribs with fabric cover

Physical Description:

NR1050. Aerobatic biplane flown by Major Alford "Al" Williams as demonstration aircraft for Gulf Oil Company. Similar to Grumman F3F single-seat fighter aircraft flown by the U.S. Navy. Wright Cyclone R-1820-G1 engine, 1000 hp.

Display Status:

This object is on display in theBoeing Aviation Hangar at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, VA.

The sturdy civilian biplane, with its strong aluminum monocoque fuselage and Wright Cyclone engine, nearly matched the Grumman F3F standard Navy fighter, which was operational at the time. It took its orange paint scheme from Williams' Curtiss 1A Gulfhawk, also in the Smithsonian's collection. Williams personally piloted the Gulfhawk II on its last flight in 1948 to Washington's National Airport.

Gift of Gulf Oil Corporation

Manufacturer: Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation

Date: 1936

Country of Origin: United States of America

Dimensions:

Wingspan: 8.7 m (28 ft 7 in)

Length: 7 m (23 ft)

Height: 3.1 m (10 ft)

Weight, aerobatic: 1,625 kg (3,583 lb)

Weight, gross: 1,903 kg (4,195 lb)

Top speed: 467 km/h (290 mph)

Engine: Wright Cyclone R-1820-G1, 1,000 hp

Materials:

Fuselage: steel tube with aluminum alloy Wings: aluminum spars and ribs with fabric cover

Physical Description:

NR1050. Aerobatic biplane flown by Major Alford "Al" Williams as demonstration aircraft for Gulf Oil Company. Similar to Grumman F3F single-seat fighter aircraft flown by the U.S. Navy. Wright Cyclone R-1820-G1 engine, 1000 hp.

Display Status:

This object is on display in theBoeing Aviation Hangar at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, VA.

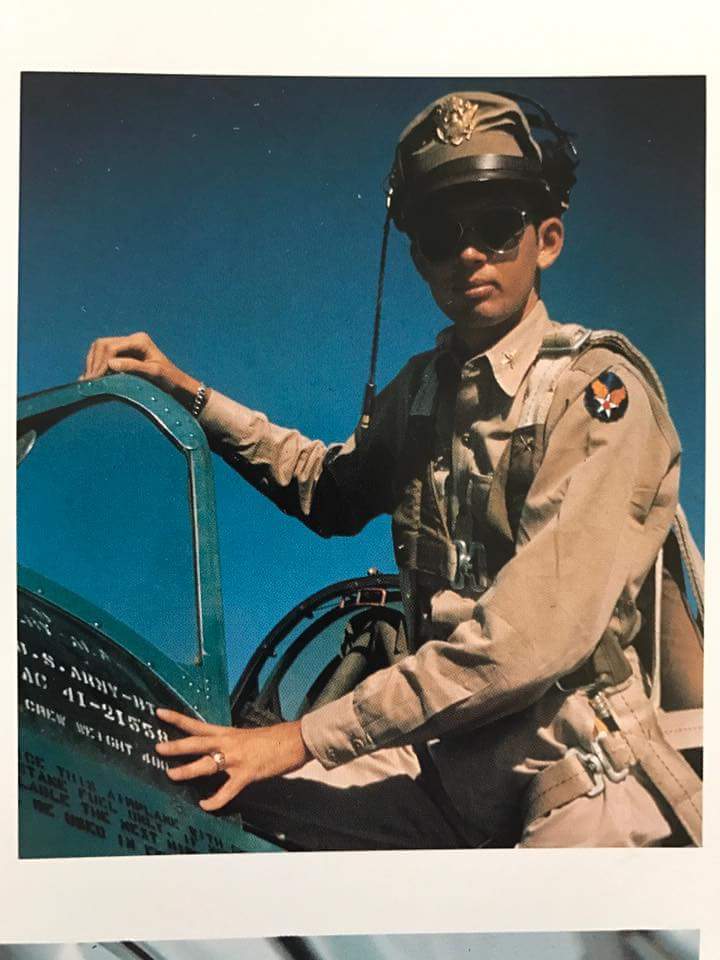

Major Al Williams' Test Flight With Bf-109D

US Marine Corps Major Al Williams, Schneider Trophy competitor with his own Kirkham-Williams aircraft, Pulitzer winner from '23 and a head of the Gulf Oil Company's aviation department, had a chance to fly the latest aircraft in the German Luftwaffe's arsenal, Messerchmitt 109 D in summer 1938. Major Williams' view on the capability of the fighter gives an interesting view on the usual commentary about flying and the capabilities of the Bf 109 fighter.

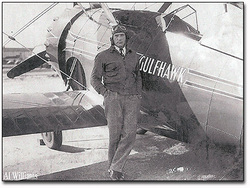

The Gulfhawk

The Gulfhawk was made-to-order for the famous stunt pilot and one time air speed record holder Major Al Williams. A former naval aviator, Williams had long admired Grumman engineering, and when he needed a new acrobatic plane, he had Grumman build it. The Gulfhawk was a highly maneuverable single-engine, biplane with a maximum speed of 290 miles per hour (467 kilometers per hour), and in Williams's hands, it performed brilliantly. During the late 1930s, it was a major attraction at air shows worldwide.

Unlike several aircraft companies whose businesses suffered during the Great Depression, Grumman had to increase its factory space and workforce considerably during the 1930s because of its military business. In 1937, the company moved to Bethpage, Long Island, and built a new factory. By the fall of 1941, Grumman had grown to approximately 6,500 workers. But the expansion did not stop there. To produce all of the planes the Navy needed during World War II, Grumman's workforce grew at a rate of 1,000 workers a month until it peaked in September 1943 at about 25,500 employees. Its floor space also increased by a factor of 25 to approximately 2.65 million square feet (246,193 square meters). Grumman plants operated 24 hours a day and produced more military planes than any other company during the war. In March 1945 alone, Grumman set the war record for the most deliveries by a single factory when it cranked out 664 aircraft.

Unlike several aircraft companies whose businesses suffered during the Great Depression, Grumman had to increase its factory space and workforce considerably during the 1930s because of its military business. In 1937, the company moved to Bethpage, Long Island, and built a new factory. By the fall of 1941, Grumman had grown to approximately 6,500 workers. But the expansion did not stop there. To produce all of the planes the Navy needed during World War II, Grumman's workforce grew at a rate of 1,000 workers a month until it peaked in September 1943 at about 25,500 employees. Its floor space also increased by a factor of 25 to approximately 2.65 million square feet (246,193 square meters). Grumman plants operated 24 hours a day and produced more military planes than any other company during the war. In March 1945 alone, Grumman set the war record for the most deliveries by a single factory when it cranked out 664 aircraft.

The Curtis Racer and The Pulitzer Trophy Race 1925

Aviation, 19 October 1925.—With the finish of the John L. Mitchell race, the crowd, which had considerably grown during the earlier part of the afternoon, waited expectantly for the Pulitzer Race, the great event of the whole meet. The atmosphere was clearing and the clouds, which, during the earlier part of the day, hung like a solid blanket over the sky, had commenced to break up. This was a very fortunate thing, for a bad haze would have proved a great obstacle in piloting the high speed planes entered in the speed classic event. The race was scheduled to start at 3:00 P. M. but both the Army and the Navy Curtiss racers were wheeled out to the starting line at least half an hour before that time.

The timers, apparently realizing the care with which these planes had to be treated, were not strict as to the exact starting time of the race. The two Curtiss racers were each equipped with high compression Curtiss type V1400 engines, said to be as nearly alike in performance as it was possible to secure. These were being given a final test while the planes stood at the starting line, with a view also to warming them up for the race.

The four planes entered, in addition to the Curtiss racers, were two Curtiss pursuits piloted by Lieutenants Cuddihy and Norton of the Navy, and a PW8 and PI piloted by Captain Cook and Lieutenant Dawson, respectively. Owing to the entry at six planes, and the possibility of trouble resulting from the hazard caused by the continual overtaking of the slower planes by the racers, it was decided by the Race Committee to divide the contest into two heats, and thus permit the two fastest planes to fly the course unhindered.

At shortly after 3 P. M. the first plane took off. It was Lieutenant Al Williams, flying the Navy Curtiss racer. His exact time was 3:14:26. He made a very smooth take-off and flew around the field for a few minutes warming up his engine.

Shortly afterward, at 3:16:39, the Army plane took off, piloted by Lieutenant Cyrus Bettis. By this time, Williams had decided to start off on the course, and, accordingly, approached the field from a far corner and, flying on full throttle, passed the timer's stand and the home pylon, being checked off by Otis Porter, chief timer.

The spectators had been expecting a close and thrilling race between the two Curtiss planes of which so much had been heard but were to be disappointed on this account, for Williams and Bettis crossed the starting line at such long intervals that all spirit of a race was entirely lost, the two planes going around the course, several miles apart. They flew at approximately 300 feet all the time. One very striking feature of the start of each plane as it crossed the line was the absence of the customary dive in an endeavor to gain excess speed. This, it will be recalled, was forbidden in this race by the National Aeronautical Association after the Dayton races last year, when steep diving over the starting line in the Pulitzer race resulted in the collapse of Captain Burt Skeel's plane, Under the new ruling this year the airplanes all approached the timer's stand in horizontal flight.

Another very noticeable feature observed as the Curtiss racers passed over the crowd on each lap was the considerable reduction in noise in this year's planes, the propellers making far less noise than those of the PW8's. With such high powered engines at the new Curtiss V 1400 and the high revolutions at which these engines run, this silencing is quite an interesting achievement.

The first lap made by Bettis was in excess of the record general average speed for this contest, which was 243.67 m.p.h. made at St. Louis in 1923. Williams' speed was also greater than this average, though by only a small margin.

The race, owing to the distance which separated the planes, had lost all recognition as such and resolved itself into a straightforward speed trial. As it progressed it was noticed that Bettis was beating his own speed at each lap, whereas just the opposite was the case with Williams, whose successive laps were getting slower with the exception of the last in which his speed for that lap reached 24366 m.p.h., or just under that for his first lap. However, his total time for the course as a whole, was still going down, as will be seen from the table of speeds.

Lieutenant Bettis' speed at the end of three laps had reached 248.7 m.p.h., virtually assuring a new closed circuit record, while Williams' speed at this lap was only 242.4 m.p.h. At the close of the race, four laps, Bettis had reached 248.975 m.p.h. and Williams 241.695 m.p.h. Thus, not only did Bettis win the Pulitzer Trophy for 1925, but, in doing so, he had set up a new world's speed record for a closed circuit. On crossing the line in the last lap, both took their planes high into the air and came around the outskirts of the field, landing and taxiing up to the enclosures.

At this moment, the four planes forming the second heat went off to compete for third place in the race. There was far more of the element of a race in the second heat, since the planes, a P1 and PW8 piloted by Lieutenant Dawson and Captain Cook of the Army Air Service, and two Curtiss pursuits flown by Lieutenants Norton and Cuddihy of the Navy, went off in close succession and chased each other at close quarters during the entire race.

As the planes started on their third lap, Dawson in the P1, which was faster than the others, was leading with Norton and Cuddihy following closely and Cook coming up fourth. It was interesting to note that the PW8's flown by Norton and Cuddihy were the same ones flown in the Mitchell Trophy race earlier in the afternoon, but from the start they commenced making much better speed than in the earlier race. Lieutenant Norton was piloting No. 50 at a speed 8 m.p.h. faster than the speed at which Matthews won the Mitchell Trophy. This fact was undoubtedly due to the difference in the length of the laps on the two races. The Mitchell Trophy course was twelve miles around, as compared with the 31.07 miles of the Pulitzer course. The former race, therefore, necessitated more and sharper turns than in the latter race and the resultant speeds for the two courses would differ accordingly.

Lieutenant Dawson still maintained a good lead as the four pursuit planes started on their final lap. He was followed by Norton while Cuddihy was compelled, by engine trouble, to drop out. Captain Cook, by this time, was at least a mile behind. The heat ended with Lieutenant Dawson finishing first, Lieutenant Norton a close second, and Captain Cook coming in third, a fact seconds later. Lieutenant Dawson's speed was 169.9 m.p.h., and Lieutenant Norton, flying a Curtiss pursuit, made 168.8 m.p.h. The speed differences resulting from the different lengths of the courses of the Mitchell Trophy race and the Pulitzer race are apparent when it is recalled that the same type of plane as that flown by Norton in the latter race made only 161.5 m.p.h. in the former.

The somewhat disappointing speeds made by the new Curtiss racers, in the Pulitzer Trophy race, may be attributed very largely to both the shape of the course and the windy weather which prevailed. The haze commenced to lift as the race drew to a conclusion and, as the two Curtiss racers came up to the enclosures, the sun began to come out and afforded a small army of photographers opportunity to get good pictures of the victors.

Post WWI

Following the war, the Navy's success with flying boats led to the design of the Navy-Curtiss NC boats, one of which, the NC-4, commanded by Lieutenant Commander A. C. Read, completed the first transatlantic crossing in May 1919. In the years to come, air racers and record breakers also grabbed the headlines, with the Navy and Marine Corps having their share of crowd pleasers. Led by perennial favorite Major Al Williams—known for his record-breaking performances in Curtiss-designed racers—Navy pilots David Rittenhouse, Rutledge Irvine, George Cuddihy, and Ralph Ofstie, as well as Marine First Lieutenant Christian F. Schilt, Medal of Honor recipient for heroism in Nicaragua, upheld their services' honor in annual competitions with Army pilots in the Curtiss Marine, Pulitzer, and Schneider Cup races.

The races of the 1920s resulted in considerable technological fallout for the Navy, as engine horsepower increased dramatically, and airframe designs by Dayton-Wright, Verville-Sperry, and Curtiss became more streamlined and sophisticated. Wood, fabric, and wire biplanes gave way to streamlined, all-metal, elegant aircraft powered by massive, in-line 500-horsepower engines. They were difficult and demanding to fly, and Navy and Marine pilots often found themselves in uncharted territory, flying with courage and intuition in a regime that eventually became the province of specially trained, experienced test pilots.

Less glamorous than air racing but essential to the future expansion of naval aviation were the Navy's long-distance flights and aerial expeditions by pioneers such as Richard E. Byrd. In May 1926, Lieutenant Commander Byrd and pilot Floyd Bennett made the first flight over the North Pole in the Fokker Trimotor Josephine Ford, a feat repeated by Byrd and pilot Bernt Balchen over the South Pole in 1929. Commander John Rogers and the crew of the PN-9 flying boat distinguished themselves in 1925 by attempting a nonstop flight from San Francisco to Hawaii. They went down in the Pacific short of their objective but, undaunted, pressed on the rest of the way under the power of sails made from wing fabric. In June 1926, the Alaskan Aerial Survey Expedition, under the command of Lieutenant B. H. Wyatt, undertook an extensive survey of unexplored regions of southeastern Alaska.

Such was the stuff of the "golden age." Navy and Marine aviators pushed the envelope and faced a world of unlimited opportunity, adventure, and challenge, unfettered by convention, regulations, and restrictions. Farsighted flag officers such as Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, first chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics in 1921, provided vital support and encouragement.

The races of the 1920s resulted in considerable technological fallout for the Navy, as engine horsepower increased dramatically, and airframe designs by Dayton-Wright, Verville-Sperry, and Curtiss became more streamlined and sophisticated. Wood, fabric, and wire biplanes gave way to streamlined, all-metal, elegant aircraft powered by massive, in-line 500-horsepower engines. They were difficult and demanding to fly, and Navy and Marine pilots often found themselves in uncharted territory, flying with courage and intuition in a regime that eventually became the province of specially trained, experienced test pilots.

Less glamorous than air racing but essential to the future expansion of naval aviation were the Navy's long-distance flights and aerial expeditions by pioneers such as Richard E. Byrd. In May 1926, Lieutenant Commander Byrd and pilot Floyd Bennett made the first flight over the North Pole in the Fokker Trimotor Josephine Ford, a feat repeated by Byrd and pilot Bernt Balchen over the South Pole in 1929. Commander John Rogers and the crew of the PN-9 flying boat distinguished themselves in 1925 by attempting a nonstop flight from San Francisco to Hawaii. They went down in the Pacific short of their objective but, undaunted, pressed on the rest of the way under the power of sails made from wing fabric. In June 1926, the Alaskan Aerial Survey Expedition, under the command of Lieutenant B. H. Wyatt, undertook an extensive survey of unexplored regions of southeastern Alaska.

Such was the stuff of the "golden age." Navy and Marine aviators pushed the envelope and faced a world of unlimited opportunity, adventure, and challenge, unfettered by convention, regulations, and restrictions. Farsighted flag officers such as Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, first chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics in 1921, provided vital support and encouragement.

Air Racing Battle, France vs. Curtiss Aircraft

By: Norm Goyer

Just as there is intense competition between the Army and Navy in all sports categories, the competition was never stronger than the US Army Air Force vs. the Navy. Caught in the middle was the Curtiss Aircraft company of Hammondsport, New York. Curtiss designers and the corporate bosses loved racing aircraft and excelled at building them. But, the US Congress wasn’t too thrilled in investing taxpayer’s money into building racing aircraft. So, Curtiss knowing how the cows ate the cabbage didn’t design racing planes they designed new fighter planes that could fly real fast with huge engines and tiny airframes, just ignore the huge racing numbers on the side of the aircraft. It was unfortunate that it was Curtiss racers competing for the Army and Curtiss racers with different numbers competing for the Navy, and they were both winning. This competition went so far that during the Schneider Cub Trophy Races the US Army was racing seaplanes and the US Navy was racing landplanes in the Pulitzer Trophy Race. Famous military pilots were involved such as the likes of Jimmy Doolittle and Al Williams. The racing plane of choice was the Curtiss R-6 and the Curtiss R2C-1. The new R2C had the top wing attached to the top of the fuselage while the R-6 the top wing was raised above the fuselage with struts. Both of these aircraft took turns winning the overall speed record and really upsetting France who for years was the country with the fastest aircraft, not the USA, but France.

The United States flying a Curtiss R-6 beat out the French with a speed of 232 mph in March of 1923.

The Third Pulitzer Trophy Race

The most impressive line-up in the history of American military air racing greeted the crowd at Selfridge Field, Mt. Clemens, Michigan, on October 14. Among the 15 starters were a dozen military racers: one Verville R-1, three Verville-Sperry R-3’s, two Loening R-4’s, two Thomas-Morse R-5’s, two Curtiss R-6’s and two

Curtiss CR-2’s.

The race, for five laps of a 50-km./31-mile course, was won by 1st Lt. Russell Maughan, in an R-6, who averaged 205.856 mph and broke every closed-course record up to 200 km. In second was 1st Lt. Lester Maitland, in an identical airplane, at 198.850 mph, while in third was Lt. Harold Brow in a CR-2 at 193.695 mph, and in fourth was Lt. Jg Al Williams, in a CR-2 at 187.996 mph. This race established Curtiss’ reputation as a designer/builder of advanced airplanes.

The Fourth Pulitzer Trophy Race

This one was run out of Lambert Field, St. Louis, Missouri, on October 6. It was for 4 laps of a 50-km./31.1-mile course. All seven starting pilots flew military racers, and all six who finished broke the old Pulitzer Race record. The winner was Al Williams, at 243.673 mph in a Curtiss R2C-1, followed by Harold Brow in another R2C-2 at 241.779 mph. The race for third place was the most exciting, Sandy Sanderson edging Steven Calloway—both in Wright F2W-1’s—by ½ second: 230.067 mph to 230.002 mph.

The Sixth Pulitzer Trophy Race

As part of what later became known as the National Air Races (October 8-13 at Mitchell Field, Long Island, New York), the sixth and last Pulitzer Race was conducted on October 12. It was flown for 4 laps of a 50-km./31-mile course. The winner, at a Pulitzer record 248.975 mph, was Cyrus Bettis in a Curtiss R3C-1. Not far behind him was Al Williams, in an identical racer, at 241.695 mph.

Schneider Trophy Article (Pre-Race)

From Aviation, October 19, 1925.

The Schneider Cup Seaplane Race

Three Nations to Compete for Seaplane Speed HonorsThe contest for the Jacques Schneider Maritime Seaplane Trophy, known as the Schnieder Cup Race, will be hed at Bay Shore Park, Maryland, near Baltimore on October 24, 1925. This trophy is now held by the U.S.Navy, having been won from Grat Britain in September 1923 by Lieut. David Rittenhouse, U.S.N. in the contest held at Cowes, England. His winning speed was 177.38 m.p.h. There was no contest for the Trophy in 1924, it being cancelled because of the lack of foreign competition.

The Navy entires in this race will be the Curtiss R3C1 racer flown by Lt. Al. Williams in the Pulitzer Trophy race and the third R3C1 racer, which was used in the preliminary test flights by both Lieutenats Bettis and Williams prior to thePulitzer race. This plane is identical with the Curtiss racers flown in the Pulitzer race itself. These machines are to be converted into float seaplanes. The Navy has also entered the Navy Curtiss R2C2, of 1923, which was converted into a seaplane last year, as a reserve.

In tirals last summer the R2C2, as a seaplane, made a speed of over 220 m.p.h., so that while the wo R3C-1 planes should prove even faster, the R2C2 will be a formidable contender if used. Lt. G.T.Cuddihy, U.S.N., and Lt. R. A. Ofstie, U.S.N. of the Plans Division of the Bureau of Aeronautics, will pilot the two R3C-1 seaplanes. Both of these pilots hold official world's seaplane records made last October at the Naval Air Meet at Bay Shore, Md., Lt. Cuddihy at this Meet, flying a Navy CR-3 racer, set the world's official record fo maximum seaplane speed at 188.82 m.p.h., and Lt. Ofstie, with a similar plane, established seaplane speed records for distances of 100 and 200 km. at 178.25 m.p.h. and for 500 km. at 161.14 m.p.h. If the R2C2 is entered it will be flown by Lt. F.H.Conant, U.S.N., of the Bureau of Aeronautics.

In addition, the Army Air Service has entered the Curtiss racer with which Lt. Cyrus Bettis won the Pulitzer Trophy this year. The plane will be converted to a float seaplane and fitted with twin floats the Army entrant should be identical with the two Navy entrants.

All the contests at Baltimore will be held uner the rules of the National Aeronautice Association and the Federation Aeronatuique Internationale, and all records made will be officially homologated.

The Navy PersonnelLieut. Comdr. H. C. Wick, U.S.N., Commanding Officer of the Naval Air Station, Anacostia, D.C., the officer in charge of the Navy Racing Detachment for Baltimore Races. Lieut. Comdr. M. A. Mitscher, U.S.N., of the Plans Division, ureau of Aeronautics, Navy Department, will represent the Bureuam of Aeronautics in the arrangements. Lieut T.P.Jeter, U.S.N., also a pilot in the Liberty Engine Builders Trophy Race, will act as liason officer for the Racing Detachment and the Bureau.

History of the Schneider CupThe Schneider Trophy and substantial money prizes were first offered by Jacques Schneider, a Franch aviation enthusisast, in 1913, when the first race for the trophy was held at Monaco. The distance to be flown in the first Schneider race was 150 nautical miles (172.83 land miles), or 278 km. This race was won by the famous French pilot, Prevost, who was flying a Deperdussin monoplane with 150 hp. Gnome engine. Prevosts's time for the 278 km. was 3 hr. 48 min. 28 sec; coresponding to an average speed of 72.6 km./hr. (45.75 m.p.h.) The 1914 Schneider Cup Race was also held at Monaco, and was over a total distance of 280 km. The race was won easily by C.Howard Pixton, who was flying a Sopwith twin-float biplane with 100 hp. Gnome Monosoupape engine. Pixton's time over the 280 km. was 2 hr. 0 min. 13-2/5 sec. corresponding to an average speed of 139.7 km./hr. (86.8 m.p.h.).

Owing to the war, no race was held until 1919, when, and English pilot having won the race in 1914, the Schneider Cup Race was held at Bournemouth, England. On the day of the race there was a thick mist over parts of the course at Cournemouth, particularly around the Swanage turning point, and all the competitos gave up, with the exception of the Italian pilot, Janello, falying a Savoia flying-boat biplane. Janello covered the prescribed number of laps, but as he was not seen from the Swanage mark boat, there was considerable discussion as to whether or not he had properly completed the course. Finally it was decided to annul the race, but as a compliment to Janello's pluck in flying round the course despite the adverse weather conditions, it was decided to award the Italian Aero Club the organization of the race for the following year.

The 1920 Schneider Cup Race was, therefore held at Venice, and was won by the Italian pilot Bologna, who on a Savoia flying boat, covered the 375 km. in 2 hr. 10 min. 35 sec., at an average seed of 172.3 km. hr. (107 m.p.h.)

Venice was again chosen as the place for the 1921 Schneider Cup Race, whcih was one of 370.4 km. The race as again won by a Savoia flying boat, piloted by the Italian, De Brianti, whose time was 2 hr. 4 min. 29 sec. corresponding to an average speed of 179.5 km. hr. (111 m.p.h.)

A British machine won the 1922 Schneider Cup. If the race had been won by an Italian pilot, the Schneider trophy would have become the property of Italy, as it wwould then have been won three years in succession. The Supermarine "Sea Lion," however won a fine victory at Naples, piloted by Capt. H.C.Baird, who is piloting the Supermarine at Baltimore this year. The Supermarine boat, which was equipped with a Napier "lion" engine, covered the distance of 370 km. in 1 hr. 34 min. 51 3-5 sec., at and average speed of 234.6 km.hr. (145.7 m.p.h.)

The 1922 race having been won by a British pilot, the 1923 race was held in England, Cowes being chosen fo the race. Only two British defenders had been built for the 11923 race, and one of these, a Blanckburn "Pellet," sank during an attempt to take off in the eliminating trials, leaving only the Supermarine flying boat to defend the cup. The British machine was hopelessly outclassed in point of speed, and the race was easily won by Lieutenant Rittenhouse, on a Curtiss-Navy Racer. Rittenhouse covered the 345 km. at an average speed of 177.38 m.p.h. (285.5 km. hr.)

A British challenger had been built for the 1924 Schneider Cup race by the Gloucestershire Aircraft Company, but this machine was wrecked during a test flight, and as no other entires presented themselves at the race, the Americans declared the 1924 race off.

This year the Schneider Cup race at Baltimore may be expected to result in the greates air races ever held.

In addition to these Curtiss racers, which are going to be fitted with floats, there are two British entires, the Supermarine Napier S4, a float type monoplane, and the Gloster Napier III, a biplane also of the twin float class. Italy will be represented by a flying boat monoplane of somewhat novel features.

A good race is expected, especially as very fine speed performance is anticipated from the British Supermarine S4 and a good contest may be looked forward to between this machine and the Curtiss Racers.

Lt. Dawson Lt. Bettis Lt. Doolittle Lt. Al. Williams

Collection of Beverly Kurts, 5-5-05

The United States flying a Curtiss R-6 beat out the French with a speed of 232 mph in March of 1923.

The Third Pulitzer Trophy Race

The most impressive line-up in the history of American military air racing greeted the crowd at Selfridge Field, Mt. Clemens, Michigan, on October 14. Among the 15 starters were a dozen military racers: one Verville R-1, three Verville-Sperry R-3’s, two Loening R-4’s, two Thomas-Morse R-5’s, two Curtiss R-6’s and two

Curtiss CR-2’s.

The race, for five laps of a 50-km./31-mile course, was won by 1st Lt. Russell Maughan, in an R-6, who averaged 205.856 mph and broke every closed-course record up to 200 km. In second was 1st Lt. Lester Maitland, in an identical airplane, at 198.850 mph, while in third was Lt. Harold Brow in a CR-2 at 193.695 mph, and in fourth was Lt. Jg Al Williams, in a CR-2 at 187.996 mph. This race established Curtiss’ reputation as a designer/builder of advanced airplanes.

The Fourth Pulitzer Trophy Race

This one was run out of Lambert Field, St. Louis, Missouri, on October 6. It was for 4 laps of a 50-km./31.1-mile course. All seven starting pilots flew military racers, and all six who finished broke the old Pulitzer Race record. The winner was Al Williams, at 243.673 mph in a Curtiss R2C-1, followed by Harold Brow in another R2C-2 at 241.779 mph. The race for third place was the most exciting, Sandy Sanderson edging Steven Calloway—both in Wright F2W-1’s—by ½ second: 230.067 mph to 230.002 mph.

The Sixth Pulitzer Trophy Race

As part of what later became known as the National Air Races (October 8-13 at Mitchell Field, Long Island, New York), the sixth and last Pulitzer Race was conducted on October 12. It was flown for 4 laps of a 50-km./31-mile course. The winner, at a Pulitzer record 248.975 mph, was Cyrus Bettis in a Curtiss R3C-1. Not far behind him was Al Williams, in an identical racer, at 241.695 mph.

Schneider Trophy Article (Pre-Race)

From Aviation, October 19, 1925.

The Schneider Cup Seaplane Race

Three Nations to Compete for Seaplane Speed HonorsThe contest for the Jacques Schneider Maritime Seaplane Trophy, known as the Schnieder Cup Race, will be hed at Bay Shore Park, Maryland, near Baltimore on October 24, 1925. This trophy is now held by the U.S.Navy, having been won from Grat Britain in September 1923 by Lieut. David Rittenhouse, U.S.N. in the contest held at Cowes, England. His winning speed was 177.38 m.p.h. There was no contest for the Trophy in 1924, it being cancelled because of the lack of foreign competition.

The Navy entires in this race will be the Curtiss R3C1 racer flown by Lt. Al. Williams in the Pulitzer Trophy race and the third R3C1 racer, which was used in the preliminary test flights by both Lieutenats Bettis and Williams prior to thePulitzer race. This plane is identical with the Curtiss racers flown in the Pulitzer race itself. These machines are to be converted into float seaplanes. The Navy has also entered the Navy Curtiss R2C2, of 1923, which was converted into a seaplane last year, as a reserve.

In tirals last summer the R2C2, as a seaplane, made a speed of over 220 m.p.h., so that while the wo R3C-1 planes should prove even faster, the R2C2 will be a formidable contender if used. Lt. G.T.Cuddihy, U.S.N., and Lt. R. A. Ofstie, U.S.N. of the Plans Division of the Bureau of Aeronautics, will pilot the two R3C-1 seaplanes. Both of these pilots hold official world's seaplane records made last October at the Naval Air Meet at Bay Shore, Md., Lt. Cuddihy at this Meet, flying a Navy CR-3 racer, set the world's official record fo maximum seaplane speed at 188.82 m.p.h., and Lt. Ofstie, with a similar plane, established seaplane speed records for distances of 100 and 200 km. at 178.25 m.p.h. and for 500 km. at 161.14 m.p.h. If the R2C2 is entered it will be flown by Lt. F.H.Conant, U.S.N., of the Bureau of Aeronautics.

In addition, the Army Air Service has entered the Curtiss racer with which Lt. Cyrus Bettis won the Pulitzer Trophy this year. The plane will be converted to a float seaplane and fitted with twin floats the Army entrant should be identical with the two Navy entrants.

All the contests at Baltimore will be held uner the rules of the National Aeronautice Association and the Federation Aeronatuique Internationale, and all records made will be officially homologated.

The Navy PersonnelLieut. Comdr. H. C. Wick, U.S.N., Commanding Officer of the Naval Air Station, Anacostia, D.C., the officer in charge of the Navy Racing Detachment for Baltimore Races. Lieut. Comdr. M. A. Mitscher, U.S.N., of the Plans Division, ureau of Aeronautics, Navy Department, will represent the Bureuam of Aeronautics in the arrangements. Lieut T.P.Jeter, U.S.N., also a pilot in the Liberty Engine Builders Trophy Race, will act as liason officer for the Racing Detachment and the Bureau.

History of the Schneider CupThe Schneider Trophy and substantial money prizes were first offered by Jacques Schneider, a Franch aviation enthusisast, in 1913, when the first race for the trophy was held at Monaco. The distance to be flown in the first Schneider race was 150 nautical miles (172.83 land miles), or 278 km. This race was won by the famous French pilot, Prevost, who was flying a Deperdussin monoplane with 150 hp. Gnome engine. Prevosts's time for the 278 km. was 3 hr. 48 min. 28 sec; coresponding to an average speed of 72.6 km./hr. (45.75 m.p.h.) The 1914 Schneider Cup Race was also held at Monaco, and was over a total distance of 280 km. The race was won easily by C.Howard Pixton, who was flying a Sopwith twin-float biplane with 100 hp. Gnome Monosoupape engine. Pixton's time over the 280 km. was 2 hr. 0 min. 13-2/5 sec. corresponding to an average speed of 139.7 km./hr. (86.8 m.p.h.).

Owing to the war, no race was held until 1919, when, and English pilot having won the race in 1914, the Schneider Cup Race was held at Bournemouth, England. On the day of the race there was a thick mist over parts of the course at Cournemouth, particularly around the Swanage turning point, and all the competitos gave up, with the exception of the Italian pilot, Janello, falying a Savoia flying-boat biplane. Janello covered the prescribed number of laps, but as he was not seen from the Swanage mark boat, there was considerable discussion as to whether or not he had properly completed the course. Finally it was decided to annul the race, but as a compliment to Janello's pluck in flying round the course despite the adverse weather conditions, it was decided to award the Italian Aero Club the organization of the race for the following year.

The 1920 Schneider Cup Race was, therefore held at Venice, and was won by the Italian pilot Bologna, who on a Savoia flying boat, covered the 375 km. in 2 hr. 10 min. 35 sec., at an average seed of 172.3 km. hr. (107 m.p.h.)

Venice was again chosen as the place for the 1921 Schneider Cup Race, whcih was one of 370.4 km. The race as again won by a Savoia flying boat, piloted by the Italian, De Brianti, whose time was 2 hr. 4 min. 29 sec. corresponding to an average speed of 179.5 km. hr. (111 m.p.h.)

A British machine won the 1922 Schneider Cup. If the race had been won by an Italian pilot, the Schneider trophy would have become the property of Italy, as it wwould then have been won three years in succession. The Supermarine "Sea Lion," however won a fine victory at Naples, piloted by Capt. H.C.Baird, who is piloting the Supermarine at Baltimore this year. The Supermarine boat, which was equipped with a Napier "lion" engine, covered the distance of 370 km. in 1 hr. 34 min. 51 3-5 sec., at and average speed of 234.6 km.hr. (145.7 m.p.h.)

The 1922 race having been won by a British pilot, the 1923 race was held in England, Cowes being chosen fo the race. Only two British defenders had been built for the 11923 race, and one of these, a Blanckburn "Pellet," sank during an attempt to take off in the eliminating trials, leaving only the Supermarine flying boat to defend the cup. The British machine was hopelessly outclassed in point of speed, and the race was easily won by Lieutenant Rittenhouse, on a Curtiss-Navy Racer. Rittenhouse covered the 345 km. at an average speed of 177.38 m.p.h. (285.5 km. hr.)

A British challenger had been built for the 1924 Schneider Cup race by the Gloucestershire Aircraft Company, but this machine was wrecked during a test flight, and as no other entires presented themselves at the race, the Americans declared the 1924 race off.

This year the Schneider Cup race at Baltimore may be expected to result in the greates air races ever held.

In addition to these Curtiss racers, which are going to be fitted with floats, there are two British entires, the Supermarine Napier S4, a float type monoplane, and the Gloster Napier III, a biplane also of the twin float class. Italy will be represented by a flying boat monoplane of somewhat novel features.

A good race is expected, especially as very fine speed performance is anticipated from the British Supermarine S4 and a good contest may be looked forward to between this machine and the Curtiss Racers.

Lt. Dawson Lt. Bettis Lt. Doolittle Lt. Al. Williams

Collection of Beverly Kurts, 5-5-05